How Reasoning (and Accident) Shape Reading: Notes on My Study and Teaching of Ethnic American Literature

By Patrick Colm Hogan, University of Connecticut patrick.hogan@uconn.edu

It appears that my engagement with ethnic American literature has been guided by more abstract considerations—and more trivial matters of happenstance—than may typically be the case. First, the happenstance. I had never studied American literature systematically. I had written some on Faulkner, due to an interest in “high Modernist” fiction (principally Joyce and Woolf). I had a longstanding admiration for Eliot’s “Four Quartets,” for its treatment of the philosophy of time. I took up Whitman due to his reworking of the Bhagavad Gita. But I had no sustained interest in American literature as such.

Why was that? In part, American literature was too much a matter of “us.” I had studied Irish literature due in equal parts to awe before the aesthetic genius of Joyce and a desire to please my parents; my mother’s hard disdain of literary study could be partially mollified by appeal to ethnic narcissism. (There were also more extended, familial reasons. My grandfather was a novelist, as well as Irish Labour Party politician; he knew Sean O’Casey, and named my father after the poet, Padraic Colum. I had an almost personal connection with the Irish Renaissance.) But I found that I couldn’t really teach Irish literature. Joyce, yes. The clientele for Ulysses was internationalist, like Joyce himself. But the one class I taught in Irish literature made me feel suffocated in the thinning air as we scaled the peaks of collective Irishness. They were smart students and nice people—probably nicer than me. But I just didn’t want to be in a group that was feeling all Irish together.

I had the same problem with American literature.

But then, over the years, students stopped taking my literary theory courses. What was I to teach? It seemed likely that only American literature had strong enough popular appeal to overcome the repellent force of my prodigious capacity to induce narcolepsy in otherwise alert undergraduates. So, I began teaching American literature.

Previously, when I had taught British literature, I had faced the issue of what distribution of works was most appropriate. Contrary to my department’s practice at the time (though with the generous support of my colleagues), I had zealously expanded Modern British Literature to include works from the empire and works by non-European immigrants. The same general considerations entered into my decisions about the scope of American literature.

Specifically, there are three broad kinds of criteria that bear on what literary works we study, in the classroom or in our scholarship. Two derive from the traditional purposes of literature, often identified as Horatian, but much more general—not only in the European tradition, but elsewhere as well. Sometimes, these are spoken of as “teaching” and “entertaining.” I will, rather, characterize these goals as ethical-political and aesthetic. The third type of criterion derives from the discipline of literary study itself. It bears on understanding, principally understanding the development of various literary works in relation to other works, movements, and so on. If I am teaching American literature, then, I have to choose works basically according to these three criteria.

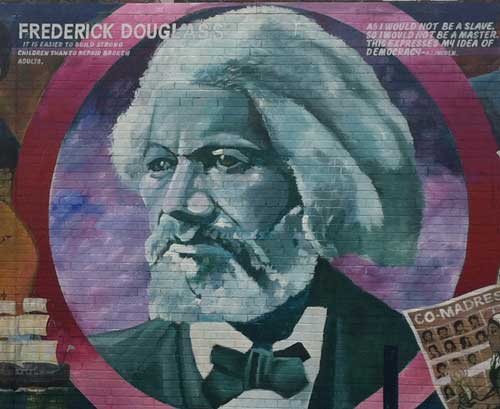

So, I might decide it is important to teach Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans or Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass for its great influence. I might choose Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying or Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain for its aesthetic excellence. As these examples suggest, works of ethnic minority literature can and should be included in literary study by both of the preceding criteria. On the other hand, they are likely to be underrepresented in both cases. The nature of racial and ethnic hierarchization in the U.S. means that works by minority authors are less likely to have commanded the attention and exerted the influence that they merited. They are, of course, no less likely to be aesthetically excellent, but the biases of dominant in-groups (e.g., European Americans) make their full aesthetic appreciation rarer. Moreover, the topic I have been asked to consider here concerns ethnic American literature as a body of texts, not particular, individual works. It is possible to choose such a body of works for, say, aesthetic reasons (e.g., relative to European American works, I might find African American poetry, plays, and novels more emotionally engaging on the whole). However, aesthetic preference is more likely to bear on individual texts. For these reasons, the political estimation of works would appear to be the most relevant in the present context.

I would distinguish three broad subdivisions of political purpose in studying literature by American ethnic minorities, or for that matter other “subaltern” groups (e.g., Dalits—former “Untouchables”—in India). Perhaps the most common reason for self-consciously choosing to study ethnic American literature in the U.S. is the empowerment of heritage students. Both “empowerment” and “heritage” seem to me unfortunate terms here, but they are the usual ones, so I use them here. “Empowerment” might at first seem to suggest an actual transmission of power. In fact, it refers to something else, or rather two other things. First, it refers to a rejection of social shaming and, commonly, an affirmation of group pride. The pride is in one’s “heritage,” which in this usage is usually taken to be ethno-racial. So, if we transport ourselves back a bit in time, we find the Irish being objects of ethno-racial denigration in American society. Individuals, identifying their heritage as “Irish” (not, say, as human), would come to feel “empowered,” first, insofar as they rejected this social shaming of the Irish and even came to feel proud of being Irish. Second, “empowerment” means conveying a sense that it is possible to overcome the social disabilities to which one’s ethno-racial group is subjected.

I used the example of the Irish here, since that would commonly be seen as my heritage group. Personally, I would like to see people identify with humanity as their heritage. After all, I had nothing to do with Yeats’s poetry. If I can feel proud of it, why not feel proud of Li Qingzhao’s poetry, to which I also contributed nothing, but which I actually find much more personally resonant. Moreover, this sort of ethno-racial pride seems to me the initial problem. Therefore, fostering it in any form seems problematic. On the other hand, I recognize that there is a vast difference between cultivating a sense of empowerment for African Americans and doing so for Irish Americans. The brutality of anti-black racism in the U.S. is almost inconceivable. And, of course, ethno-racial stereotyping and hostility are not limited to African Americans by any means. Clearly, empowerment of demeaned and endangered groups is ethically and politically necessary. That does not mean it is not problematic even in those cases. But it does mean that the source of the problem is ethno-racism from the dominant group and thus white critics (such as myself) are ethically and politically obligated to oppose hegemonic ethno-racism (the great plank in our own eye), rather than quibbling over the relatively minor problems of empowering subaltern groups (the mote in our brother’s or sister’s eye). Even so, I must admit that, in my own case, such empowerment is not a strong, personal reason for teaching and studying ethnic minority literature of the U.S.

The second common political reason for a focus on ethnic American literature concerns ideological critique, the opposition to dominant ethno-racial ideologies (e.g., the stereotyping of African Americans). Such critique has two elements. The perhaps more obvious component is informational. It is a matter of representing cultural practices, social relations, and material conditions of the group in question. I do not hold to the view that an author automatically represents his or her ethno-racial in-group accurately and out-groups with ideological bias. Everyone’s experiences of in- and out-groups are limited and to some degree biased. However, put simply, African Americans are more likely to share some distinctive experiences (e.g., of white racism) with one another and are more likely to see other African Americans as members of their in-group, rather than as outsiders. Though far from infallible, such tendencies are likely to provide at least a valuable corrective to the sorts of distortion that are likely to affect European American writings about African Americans.

The other component of ideological critique is perspectival. It involves the cultivation of a reader’s capacity and inclination to take up the point of view of someone from the relevant ethno-racial group. In other words, it is a matter of cultivating our effortful cognitive and affective empathy with a person from that group. This absolutely does not mean that we understand the group as a whole, or even that we have acquired a good sense of somehow prototypical cases. But that matters less than the fact that we have been guided by the author to simulate the subjectivity of someone whom we might otherwise have dismissed thoughtlessly. Here, too, white authors can and do at times cultivate such perspective-taking across ethno-racial identity divisions. However, the factors mentioned in the previous paragraph suggest that ethnic minority authors are likely to provide perspectives that to some degree complement those provided by white authors, correcting the latter, even when they are (differently) imperfect themselves. Another way of thinking about the issue is in terms of interpersonal stance. Interpersonal stance is our emotional attitude toward the experiences of another person or group of people; it governs, for example, whether we feel sympathy or Schadenfreude when faced with someone else’s pain. Studying a range of authors with different ideas and perspectives—prominently including ethnic minority writers—is one possible means of altering our interpersonal stance, not only toward characters, but (ideally) toward members of the relevant social identity group in real life.

The final political reason is, so to speak, the “thinnest,” the one that involves the least significant political claims. However, it is arguably the most compelling. It is simply democratic representation. American literature includes authors from a diverse array of groups. Though it varies somewhat with our exact purposes (e.g., whether we are focusing on a particular theme, region, period, genre, or whatever), we would seem to have a prima facie obligation to select authors who are reasonably representative of the general literary populace. Indeed, this is likely to promote the political goals just discussed, but without the need for invoking political justifications, beyond favoring democracy—which, one hopes, is not a controversial preference for anyone studying American literature of any sort.

As it turns out, then, my apprehensions about the unbearable us-ness of U.S. literature were misplaced. Any body of literature has perspectival diversity and ideological complexity, which becomes clear even when one approaches the literature with just a basic concern for democratic representativeness. On the other hand, I still feel the need to qualify that concession and affirm the importance of reading outside one’s social identity categories, and hoping for a future society in which global identifications can displace those categories. Even with my appreciation of Walt Whitman and Amiri Baraka (with their sometimes particularistic, sometimes more global identifications), I remain closer in spirit to grieving Li Qingzhao or the simultaneously isolated and universe-embracing Li Bai.

Patrick Colm Hogan is a Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor in the English Department, the Program in Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies, and the Program in Cognitive Science at the University of Connecticut. He is the author of numerous books, including American Literature and American Identity from the Revolution through the Civil War: A Cognitive Cultural Study (Routledge, forthcoming).