By Mario Grill

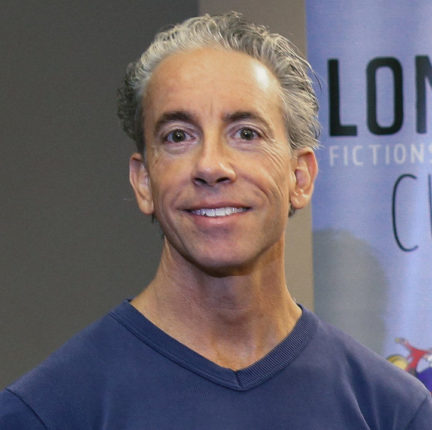

Frederick Luis Aldama is a cognitive cultural studies scholar and one of the leading figures in Latinx Studies. His work is therefore of central importance to our research at the Narrative Encounters Project.

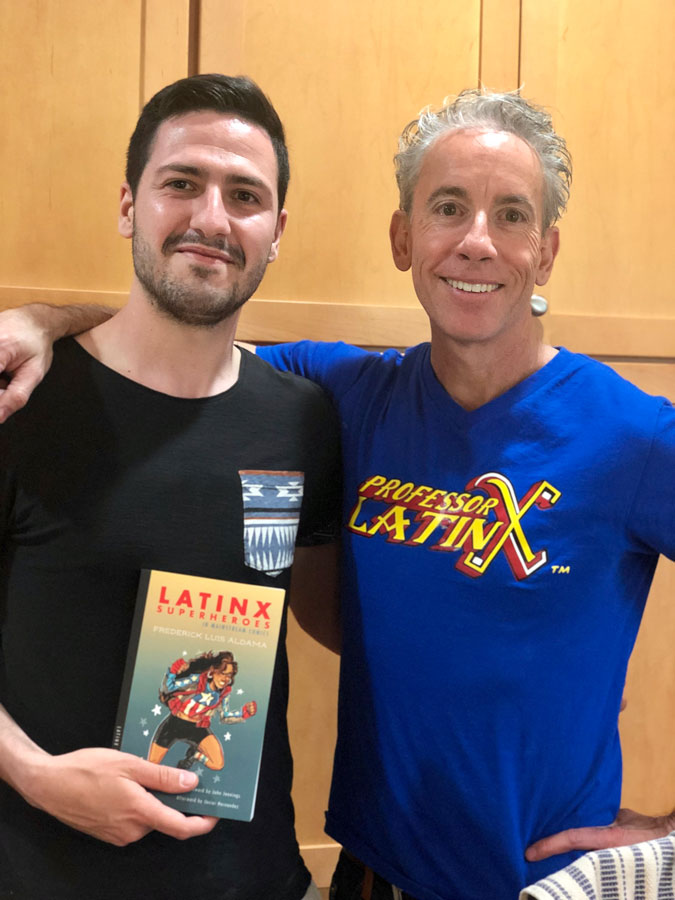

As Arts & Humanities Distinguished Professor, he teaches Latinx literature, comics, film, and pop culture at The Ohio State University. He is also an affiliate faculty of the Center for Cognitive and Behavioral Brain Imaging as well as co-founder and core faculty member of OSU’s Project Narrative. He is the recipient of the Rodica C. Botoman Award for Distinguished Teaching and Mentoring as well as the Susan M. Hartmann Mentoring and Leadership Award and he is founder and director of the award winning outreach center at OSU, LASER: Latinx Space for Enrichment & Research. He is founder and co-director of Humanities & Cognitive Sciences High School Summer Institute. Togetherwith his brother, Arturo Aldama, and Patrick Colm Hogan, in 2005 he established the Cognitive Approaches to Literature and Culture series at the University of Texas Press; he currently continues to co-edit this as the Cognitive Approaches to Culture Series with Ohio State University Press. He is editor and coeditor of 8 additional academic press book series as well as editor of Latinographix, a trade-press series that publishes Latinx graphic fiction and nonfiction. He is the award-winning author, co-author, and editor of 36 books. In 2018, Latinx Superheroes in Mainstream Comics won the International Latino Book Award and the Eisner Award for Best Scholarly Work. Aldama’s other book publications include: Your Brain on Latino Comics: From Gus Arriola to Los Bros Hernandez (2009), Latino/a Literature in the Classroom: Twenty-first-century Approaches to Teaching (2015), The Routledge Companion to Latina/o Popular Culture (2016), and Latino/a Children’s and Young Adult Writers on the Art of Storytelling (2018). You can read more about his work and life here: www.professorlatinx.com

During a visit to The Ohio State University in April 2019, I had the pleasure of interviewing Professor Aldama. We spoke about his work as well as potential developments in cognitive literary studies focusing on Chicanx literature. Here is the first part of the interview. The second and third part will follow in separate posts.

Setting the Tone and Cognitive Cultural Studies

MG: In both your teaching and scholarship, you use narrative theory, cognitive science, and insights from Latinx and Latin American cultural theory. What would you say are some of the benefits of working on the intersection of these disciplines and cultures and how can such interdisciplinary cross-fertilization enrich our understandings of ‘the other’?

FLA: First, let me say thank you, Mario, for this interview and for clearing the space to talk about this. Okay, so something happened when I was an undergraduate at Berkeley that came into sharp focus as a graduate student at Stanford. I was extremely excited about Latinx literature and film and the study of it but I wanted to get at the kind of roots, the deeper, say, foundations of where creativity comes from: how we can create as Latinxs and as human beings generally. I wanted to understand better how is it that our brain has evolved the capacity to imagine, to sculpt a story imagined in the mind, then to realize materially this story either through typing of fingers to create words on a page, using sound and cameras to make a film, or using pencil and paper to geometrize narratives in the form of comics.

How do we begin to get at an understanding of the foundations of creativity and storytelling? Well, first of all, cognitive sciences has made tremendous breakthroughs in this area; it’s no longer a deterministic science. It is an exploratory and richly expansive science. The neurosciences, especially the subfield of neuro-aesthetics as informed by the advances in neurosciences, has been also extremely fruitful. With these research advances, we can understand better how we create and how our brains/minds work to step into storytelling schemas and then radically revise those schemas. Whether you are in a movie theater or reading a comic book, today we can better understand how perception and our senses translate information into both emotion and intellectual imaginative responses. To get at this knowledge foundation I had to go the sciences.

As far as narrative theory goes, well, already as an undergraduate at Berkeley I was drawn to courses taught by Seymour Chatman. Of course, these supplemented important courses on Chicanx (taught by professors Alfred Arteaga and Genaro Padilla) and African American literature (the late Professor Barbara Christian). As an undergraduate I found Chatman’s attention to story and discourse extremely generative; I also found Professor Robert Alter’s courses on style extremely productive. The tools and concepts of narrative theory allowed me to go beyond just character or thematic analysis. It allowed me to see not only how authors give respective shape to their Chicanx narratives but also how they build signposts into their fictions that, once the text is in the world, are co-constructed by readers like myself. Narrative theory continued to be an important part of my conceptual diet as I moved increasingly into the study of Latinx films and comic books. It continues to inform my writing and teaching, deepening an understanding of all of the shaping devices that are used by creators to make stories interesting, engaging, and alive. Narrative theorists over time have been able to refine and add to the kind of periodic table of shaping devices so that we can kind of see better what is going on both in film, comic, and literature. It’s not surprising that I found myself gravitating toward narrative theory. It’s the natural space for kind of analysis that I was hungry to use in my work and in my classrooms as a professor.

MG: You bring us to issues and debates regarding cognitive cultural studies. This approach is often criticized for focusing too narrowly on the interaction between a text and a single, highly abstract reader, neglecting the cultural and ethnic diversity of the actual audiences. What do you think of this critique and how would you argue against it since this is coming up again and again?

FLA: Anytime you mention “science” someone is going to have a quick knee-jerk reaction. For them, science is a stand-in for universals and essentialism that has been used to erase regional, ethnic, racial, gender, sexual differences. It will obliterate the intersectionalities and specificities that make up our vary varied human condition. With long histories of science being used to justify racism, sexism, and homophobia, believe me, I get it. Today, we’re seeing something new, as I already mentioned. We can go to the cognitive sciences to explore and enrich in non-deterministic ways. Indeed, these insights can bolster our positions against racism, sexism, classism, and homophobia.

But let me take us to one of the deep reasons why I found my way to the cognitive sciences. I wanted to insert myself into the foundations of epistemological equations. The foundations that we have evolved as a species for thousands of years; foundations that have allowed us to create a multinetworked brain that allows our emotion system to interface with our prefrontal cortex when we create fiction, for instance. I am asking questions that are at the foundations—the roots, if you will—of who we are, how we are in the world, and how we create and transform the world.

Now, of course, these are going to express themselves uniquely, as uniquely as each of us are a unique person in this world. But if you start at the ends of the branches, your work will forever be infinite. It’s fine to work at the ends of the, say, many thousand branches that have grown from the roots, but one might never get at the foundations that I’m interested in knowing more about.

So, bottom-line is: Yes, we are all born with innate capacities for the growing of a language faculty (I am totally on board with Chomsky), long and short term memory processes, the growing of emotion systems and so on. And, yes, these innate capacities will grow in extraordinarily unique ways within specifics of time and place; they will grow into the many different personalities that make up the world. Those are definitively shaped by things like your race, your ethnicity, your gender, and as we grow and come into, our sexuality all of these things are going to inform and shape the kind of expression of this universal stuff that we all share.

MG: This means that you would also agree that fictional narratives invite our readers to step into the imaginary shoes of a character that is slightly or uniquely different from them and allows them to see what such a life may be like. Would you say that all ethnic American literary texts do so using the same methods? Or, are there distinct differences in how this happens, for instance, in Chicanx or Latinx literature to be more general?

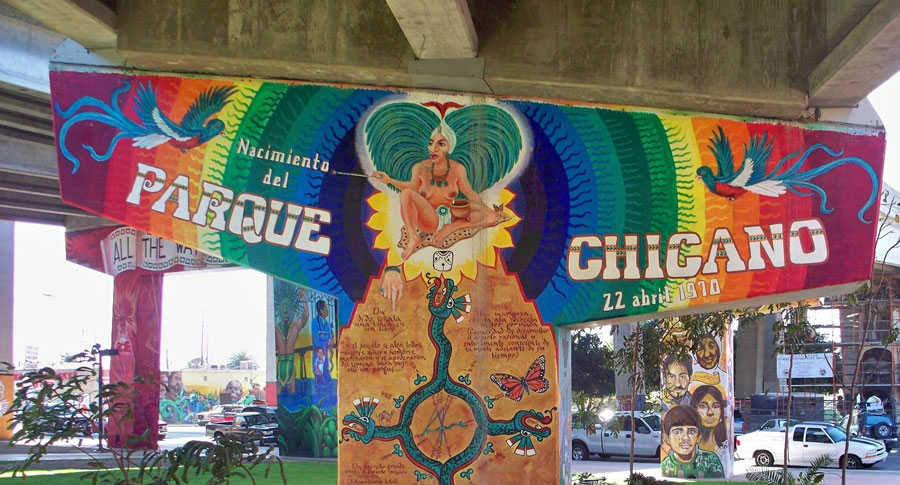

FLA: Yes, you are right, I mean basically literature, film, comics all invite anybody to engage with them on a deep level: to co-create and co-imagine. Of course, different creators might have different ideal audiences in mind. With someone creating a specifically Chicanx comic book superhero, there are going to be elements that anybody can step into and understand and feel. There are also going to be, depending on the degree of will and specificity on the part of the creator, things that an outsider to Chicanx culture might not get. And, different creators decide if they will or how they will educate outsider readers.

Coco (2017) is a good example: It had a huge, deep, appeal with Chicanx and Mexican (in Mexico) communities and families. In fact the big numbers in terms of box office sales came from our communities. At the same time, it also appealed to many many non-Chicanx and Mexican audiences. When we create, we can make a narrative fiction we can have a singular, restrictive ideal audience in mind. We can also have multiple ideal audiences. And, at the end of the day, because we share common ground in terms of our faculty for imagining, feeling, and thinking, no matter if more restricted or expansive in terms of built-in ideal audiences, narrative fiction always opens its arms to everybody.

Part II >

Mario Grill