“Spooling Out: A Thousand and One Reading Experiences Professed by a Black Bookworm”

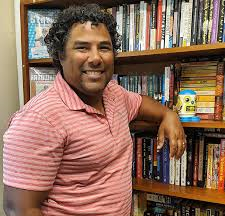

Hello, my name is Isiah Lavender III and I’m a self-confessed bibliophile. I believe it is my duty to disrupt the imperial gaze by exploring BIPOC futures arising from non-Western cultures and ethnic histories. Viewed in this way, I help the world to understand that BIPOCs live in the future too, that we can reboot identity in the creation of CoFutures. But to arrive in these full-colored futures, I must reexamine my path that led me to the Sterling-Goodman Professorship at the University of Georgia. Suffice to say, I simply love reading. And, I want to demonstrate the value, power, stretch, connection, integration of reading in my life. Let us deep-dive, you and I, into an aspect of my own personal reading history.

In this respect, I’ve been asked to think about my personal reading history in ethnic literatures and found that I have a lot to say. But this reflection requires a way back machine across the 47 years of my life. It’s not unlike travelling in Dr. Who’s TARDIS, only this time piloted by the Thirteenth Doctor (Jodie Whitaker) since I’m not being asked about my keen interest in science fiction but questioned about my passion for reading ethnic literatures.

You probably wouldn’t be shocked to discover that both of my parents were avid readers. Dad loved westerns and had a bookshelf full of Louis L’Amour novels and I fully availed myself of them when not playing with my Star Wars action figures. At one point, I could probably tell you all there was to know about the Sackett family and their generational adventures on the American frontier. The character of Jubal Sackett comes to mind because he went in search of an Indian woman named Itchakomi. I think she was Natchez or Cherokee, possibly Choctaw. I may have been 7 or 8 at the time, but this novel made an impression on my mind. It stayed with me because my African American grandmother Cornelia swore that my black curls supposedly came from a Cherokee ancestor sold into slavery in Virginia in the mid-nineteenth century and not from the white side of my family. Incidentally, I’m a sixth generation Lavender removed from the American antebellum era with my ancestors enslaved near Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and have often thought my hair texture resulted from a long-ago sexual assault. That seems more likely, but who knows?

Anyway, my first-generation American mom of Austrian/Polish descent (a dissolved Prussian) absolutely loved science fiction and fantasy, which I have talked about elsewhere, but also enjoyed reading romance novels by Harlequin Enterprises and Avon Historical Romances, or bodice-rippers as I like to think of them in popular parlance. Did I read them? Yes. Yes, I did. Her favorites authors were Johanna Lindsey and Bertrice Small. I know that I encountered an Arab sheik named Sheik Abu in Lindsey’s Captive Bride (1977) and a multitude of savage Indians in Tender is the Storm (1985) as a nineteenth century New York heiress, named Sharisse, heads west to Arizona as a mail-order bride and even more Indians in Brave the Wild Wind (1984), the first book in Lindsey’s Wyoming Westerns series.

Some characters just stay with you. My personal favorite was Small’s first Skye O’Malley novel from 1981, as this Irish noblewoman creates a shipping empire, rivals Queen Elizabeth herself, and challenges the Ottoman empire after being captured and sold to Khalid el Bey, the whoremaster of Algiers. Undoubtedly, I must have come across the Italian fashion model Fabio on one of these book covers (smile)! I must have been between 10 and 12 at this time. Understand, I would read anything and everything up to and including my older sister’s Sweet Valley High books and the Baby-Sitter’s Club and the Flowers in the Attic series by V.C. Andrews (the Dollanganger series I think it’s called)on top of my own Hardy Boys, Choose Your Own Adventure, Twistaplot, and Endless Quest books. I was that kid and I was fascinated by the worlds I came across and in which I got lost.

My parents also had an extensive library of classic British and American literature downstairs in our basement—extensive to my child eyes since the hanging bookshelves ran the length of one wall, from the ceiling to a foot off the ground, with the books flush against the concrete. While I didn’t make it through Moby Dick until graduate school, I did read a bit of Poe and Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847) and Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847) among many other books of this nature like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) if memory serves correctly. I guess my parents belonged to some kind of mail-order book club that produced cheap hardbacks of literary classics with gold-leaf lettering on the spines and covers of the black volumes, published by the International Collectors Library in Garden City, New York. Likewise, I took advantage of the opportunity to thumb through what seemed like a countless number of National Geographic magazines. We also went to the Hamburg Public Library a great deal and, less frequently, the much larger Buffalo Public Library.

Beyond a shadow of a doubt, my two favorite novels from this grand home library of my childhood were Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and its sequel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884). In fact, I still have that copy of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. It’s one of my few surviving childhood possessions and it’s prized!!

I loved Tom and Huck and had similar adventures of my own in the hamlet of Derby contained in the town of Evans, a south town of Buffalo, New York, infamous for the lake-effect snow. I’d often go looking for buried treasure hidden in the woods behind my house with my childhood friends in the early 1980s, build extensive woodland forts, and get in pitched battles with the kids in the Redwood townhomes across the “Big” Creek—Apple Wars I & II, the Pear War, and even the Cattail War fondly live on in my memory as it all runs together. In many ways, I had a rich childhood in western New York on the shores of Lake Erie close to the Canadian border. Just like Tom, we would sneak out after dark, use the meow of a cat at a friend’s window, and go off in search of treasure. That was my idea too! We did not come across the murdering Injun Joe at a midnight graveyard, but we did see teens smoking pot, drinking, and necking in the woods near the old private road across the “Big” ditch. Like Huck and Nigger Jim, we once built a raft out of some old one-by-fours and attempted to float down the “Big” creek through the woods to the dam close to Old Lake Shore Road. Again, my idea! I knew Jim was black like me but also a slave. That was my context! My impression of Native Americans at this time of my life was based on caricatures and stereotypes. I was in for a rude awakening—a racial awakening in the winter of 1983. I’m actually not sure when I read Tom Sawyer or Huck Finn with respect to the “n-bomb” dropping but it must have been around 4th grade because I didn’t have the raft idea until after the spring class trip to Eighteen Mile Creek to hunt fossils in the gorge.

I have written about my first moment of “epiphanal blackness” elsewhere (Williams 173). “Epiphanal blackness,” to use Piper Kendrix Williams’s term, refers to the first time a black person is made aware of their own skin color in being called a nigger by a white person. I have already written about this difficult moment in my own life and its relationship to my penchant for reading science fiction beginning with Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles (1950). But that’s only half of the story in my autography of reading. That moment also spawned my abiding love for fantasy fiction, which I don’t write about in a scholarly fashion although I am currently loving Evan Winter’s The Rage of Dragons (2020) and its sequel The Fires of Vengeance (2021). That moment of being beaten bloody by white boys in front of my house and called a nigger will never be forgotten. I was eight years old.

This shit goes deep!

But even pinpointing this particular instant as my first dawning of racial consciousness may be inexact and fuzzy because of my placement in remedial reading class in second grade during the fall of 1981 when I was seven. What else could it be other than institutional racism? The only black kid in the entire second grade of Highland Elementary in the slow reading group?! Hmm…. I have never been indifferent to pleasure reading and this moment was huge! I am ever grateful to Mrs. Ennis who had me out of there and into the gifted program inside of six weeks and I will always sing her praises. I could also talk about the super tag team duo of Mrs. and Mr. McDonald from eleventh and twelfth grade here—headstands on desks, creative writing assignments, fascinating group projects, and whatnot—because they taught me a great deal about writing and pleasure reading, but, really, that’s another story for another time. The power of teachers to do good amazes me sometimes. Let me stress that reading for school is different to reading for self and we all know it. Alongside my parents, these three are immortal members of my own pantheon of illustrious beings just like my school bus driver Jonie.

Jonie stopped the bus after rounding the court and prevented the pack of fourth-grade boys from doing further damage in the gray February snow drifts of that yesteryear afternoon. Long story short, my parents went ballistic at the PTA meeting and I had to ride at the front of the bus in the first seat right behind Jonie for the rest of third-grade. I guess I shouldn’t have mouthed off that morning at the bus stop to those boys, but I did! Oh, the impetuosity of youth! Nevertheless, it was Jonie who introduced me to Bilbo Baggins by recounting his encounters with Sméagol and Smaug one day while waiting for the bus to load. I told my Dad, and The Hobbit (1937) magically appeared on my pillow before bedtime later in the week. He bought me the book and I was immediately entranced by orcs, goblins, trolls, hobbits, elves, dwarves, dragons, and, of course, Gandalf the Grey! Fantasy is deeply steeped in racial discourse and I have voraciously consumed it from this moment onward. I started playing Dungeons and Dragons that year too with a small group of my friends.

This essay seems to be getting away from me as I put these fractured memories into a semblance of order, but it all relates to my reading practice. Just like my time playing indoor soccer on the Seneca Nation of Indians Reservation in Irving, New York near Cattaraugus Creek right down the Route 5 Highway. You see, I may have been one of the only black kids in my grade school days, but there were plenty of Res kids at my school (Jimersons, Smiths, and Maybes). One of them and I used to good-naturedly jibe each other as “spear-chuckers” throughout high school in the hallways of Lake Shore Central Senior High. I loved a good verbal joust every now and again and didn’t realize the psychic damage we inflicted on each other performing for our classmates. On one occasion, our oral sparring went too far! I got under my buddy’s skin with an aural dart. He grabbed me by my shirt collar, lifted me off the ground, and slammed me into the lockers. He was a defensive lineman on the varsity football team. I think moments like these are exactly why I am captivated in reading Native American literature—ill-spent youth, where my mouth got me into trouble, dreaming of being Bruce Lee to defend myself with Kung Fu, though I never studied any martial arts.

I can recall being fascinated by the Iroquois Creation myth, visiting the Turtle in Niagara Falls, seeing it enacted, and studying the Iroquois Confederacy in ninth grade history class right along with the Civil Rights movement. I would later teach the orature account of this powerful creation myth in Am Lit I classes. I easily recall being blown away by Louise Erdrich’s (Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians) Love Medicine (1984), particularly the often anthologized “The Red Convertible” as well as the nightmare scene, where the main character, Victor, recalls soldier’s playing polo with an Indian woman’s skull in Sherman Alexie’s (Spokane/Coeur d’Alene) story “The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven” (1993). I also attempted to teach Gerald Vizenor’s (White Earth Band of Ojibwe) Bearheart: The Heirship Chronicles (1990) to a highly conservative classroom of University of Central Arkansas students and failing miserably not to mention Daniel H. Wilson’s (Cherokee) Roboapocalypse (2011), Stephen Graham Jones’s (Blackfeet) The Bird is Gone: A Manifesto (2003), and Leslie Marmon Silko’s (Laguna Pueblo) Ceremony (1977), among many others of my more successful attempts to expose students to Native American literatures. The most recent successful efforts would include Rebecca Roanhorse’s “Welcome to Your Authentic Indian ExperienceTM” (2017), Cherie Dimaline’s (Métis) The Marrow Thieves (2017) and Waubgeshig Rice’s (Anishinaabe) Moon of the Crusted Snow (2018). And, so, I have learned many lessons from reading ethnic literatures.

Earlier, I briefly mentioned Bruce Lee and Kung Fu and can surely trace my desire to read Asian literatures to Kung Fu Theater on Saturday afternoons (Fists of Fury (1972) to name only one) and to the Japanese anime appearing on American and Canadian television airwaves in the late 1970s through the mid-1980s such as Star Blazers, Battle of the Planets, and Robotech among others. I spent countless Saturdays watching English-dubbed martials arts films and space battles with aliens and giant robots. And I would watch more in undergrad, too, like Bubblegum Crisis, Ninja Scroll, Ghost in the Shell, Akira, and Evangelion as well as falling in love with the black hip-hop group Wu-Tang Clan. But that’s beside the point. These experiences would lead me to read and teach many different things from The Epic of Gilgamesh, Monkey, and the Ramayana to Kobo Abé’s The Box Man (1973), Koushun Takami’s Battle Royale (1999), Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club (1989), and John Okada’s No-No Boy (1957) as well as, and more recently, Ling Ma’s Severance (2018), Chen Quifan’s The Waste Tide (2013), Anil Menon’s The Beast with Nine Billion Feet (2009), and Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem (2014).

If you expected me to name Chinua Achebe as representative of my African reading experiences, you wouldn’t be wrong. I can think of no better starting place for any person interested in global Anglophone literature than Things Fall Apart (1958). Who’d have thought that Achebe would have clapped back across time at Victorian author Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness (1899) and its soul-crushing depiction of Africa as the dark continent by quoting half of the third line of Irish poet William Butler Yeats’s “The Second Coming” (1919)? What a magnificent intertextual smackdown! Of course, the Irish were considered another black race at some point in Western history. See Noel Ignatiev’s study How the Irish Became White (1995) if you don’t believe me! Anyway, back to Africa, you would have to tack on the D. T. Niane translation of Sundiata: an Epic of Old Mali as well as writers such as Ama Ata Aidoo, Buchie Emecheta, Bessie Head, Wole Soyinka, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Nadine Gordimer, Athol Fugard, and Amos Tutuola (and most recently Tade Thompson’s Wormwood trilogy beginning with Rosewater (2018) and Namwali Serpell’s The Old Drift (2019)) to begin sensing what stories from the continent mean to me. There are others too.

I could do a similar thing with my experiences of Latinx literatures and name Gloria Anzaldúa, Sandra Cisneros, and Piri Thomas as foundational authors as well as Malka Older and Junot Diaz as more recent Latinx writers of the sci-fi variety. Writers teach us to see ethnic peoples as human, to see beyond cultural stereotypes to the vibrancy of living, to dare make friends despite the differences.

I could also do a comparable thing in naming and listing some of the black Caribbean writers, poets, and thinkers I have read such as Jamaica Kincaid, Derek Walcott, Sylvia Winter, Édouard Glissant, and Edwidge Danticat without forgetting the Caribbean science fiction writers Nalo Hopkinson, Tobias Buckell, and Karen Lord. I could do so, but I shan’t because I’m already well past the 2000-word limit!

I’d also like to write about my expansion into Arabic speculative fictions such as Ahmed Saadawi’s Frankenstein in Baghdad (2014), but I realize it would tie back to Epic of Gilgamesh and also my reading of Arabian Nights. Like Scheherazade, I have a thousand and one reading experiences of my own to tell.

Now, “learn it to the younguns” as the grandfather declares with his dying breath in Invisible Man (Ellison 16). I’ve always wanted to use that quote and now I have! That’s just why I am a black bibliophage. This now feels like a declaration, strangely thrilling, freeing! The life- stories will continue…spooling out.

Works Cited

Ellison, Ralph. Invisible Man. 1952. Vintage, 1995.

Williams, Piper K. “Harriet Tubman’s Shawl.” The Toni Morrison Book Club, Juda Bennett,

Winnifred Brown-Glaude, Cassandra Jackson, and Piper Kendrix Williams, U of Wisconsin P, 2020, pp. 166-180.

Isiah Lavender III is Sterling Goodman Professor of English at the University of Georgia. His book publications include Race in American Science Fiction (Indiana University Press, 2011), Black and Brown Planets: The Politics of Race in Science Fiction (University Press of Mississippi, 2014), Dis-Orienting Planets: Racial Representations of Asia in Science Fiction (University Press of Mississippi, 2017) and Afrofuturism Rising: The Literary Prehistory of a Movement, has just appeared from Ohio State University Press (2019).